The head of Formula 1, Stefano Domenicali, is considering a reduction, or even complete removal, of free practice sessions during a Formula 1 weekend.

For someone of my experience, this comes as a shock. I am still nostalgic for the pre-race warm-up sessions, and if my professional path hadn’t led me to motorsport journalism, I believe I would still be lamenting their absence more than two decades after those thirty-minute periods of track activity were discontinued.

My perspective as a journalist isn’t about regretting the removal of the warm-up in F1 or sportscar racing. From a work standpoint, they weren’t necessary; in fact, they sometimes complicated my work in the paddock.

However, as a spectator attending races, I would have been disappointed by the omission of that brief period of track action on race day morning. These warm-ups were integral to my experience as a fan.

I preferred to have some insight before the race began. This wasn’t as crucial at the British Grand Prix, where I was familiar with the cars from television, but it was more significant for events like the world championship sportscar race at Brands Hatch. I wanted the chance to observe the cars before the race started, to learn to identify them before they appeared at the crest of Paddock Hill Bend on the first lap.

Driver rosters changed, as did liveries, during those less uniform times, and occasionally even the appearance of the vehicles themselves.

Stefano Domenicali, Chief executive officer of Formula 1

Photo by: Marco Canoniero / LightRocket via Getty Images

Consider the front wing that appeared on Richard Lloyd’s Porsche 956 during the Brands Hatch 1000 km round of the WEC in 1984. Imagine my confusion if I had only glimpsed that addition – created from a Ralt Formula 3 wing, as I later discovered – during the warm-up lap. I would have been completely perplexed as I prepared for the charge towards Paddock at the start. It would have disrupted my lap-charting!

I have a strong fondness for my experiences watching race-day warm-ups from the spectator side. There’s something uniquely captivating about the early-morning atmosphere at a British race circuit, the excitement of engines starting up for the first time that day, the lingering scent of fried breakfast in the air.

Without those warm-ups in my younger days as a spectator, I wouldn’t have had the chance to see the Lotus 80 in action. That beautiful creation, Lotus’s short-lived attempt to improve upon the type 79, only participated in three races and six F1 events in 1979 before being retired.

I can proudly say I witnessed one of those events, the non-championship Race of Champions at Brands Hatch that year. I have a rather poor photograph of it somewhere, taken with my Kodak Instamatic at the age of eleven, to prove it.

And I had the privilege of seeing the Cosworth-powered Lotus 80 before its sleek lines were marred by a rear wing. The ground-effect tunnels running almost the entire length of the car were intended to eliminate the need for one, although by the time it achieved its only podium finish at Jarama in Spain, it had acquired a conventional wing at the rear.

Mario Andretti was entered in the type 80 for a race hastily arranged for the weekend following the Long Beach GP in April after the original event was cancelled due to snow. Throughout the weekend, he switched between the 80 and the 79, ultimately choosing the reliable car that had secured his F1 title the previous year, after a final test of the new car during the warm-up.

And spare a thought for the Nelson Piquet fan who was watching near me at the same event four years later in 1983, the last non-championship race in F1 history. This individual, dressed like the president of the Brazilian driver’s fan club – and potentially was, for all I knew – didn’t seem to recognise his hero’s helmet design.

1983 Race of Champions

Photo by: Motorsport Images

Piquet was initially listed in the solo Brabham-BMW BT52 in that week’s Autosport magazine, but at some point, he decided to withdraw from a minor race contested by only thirteen cars. His replacement was Hector Rebaque, the Mexican driver rejoining the Brabham team after an absence of more than a year from the team and F1.

Rebaque didn’t distinguish himself that weekend in the car that Piquet would later drive to the championship title. He performed poorly in qualifying (10th out of 13), in the race (the team allegedly deliberately dropped the car off its jacks during a pitstop to end his race), and in the warm-up (he spun at Paddock right in front of me and the aforementioned fan).

It was only after Rebaque emerged from the BT52 following his spin that the fan next to me at Paddock realised his idol wasn’t participating that day. While he might not have recognised Piquet’s helmet design, he certainly knew what Nelson Piquet looked like.

What would have happened if there hadn’t been a warm-up at Brands that day? Would our enthusiastic supporter have spent the race cheering for Piquet, wondering why the 1981 world champion was so far off the pace in a car in which he had triumphed in the season-opening race in Brazil?

There is a serious aspect to this discussion, though. I acknowledge that F1 CEO Domenicali wasn’t considering my personal preferences when he proposed changes to the race weekend format. I’m probably too old for that. However, I maintain that the appeal of motor racing, or any sport, isn’t solely based on immediate excitement.

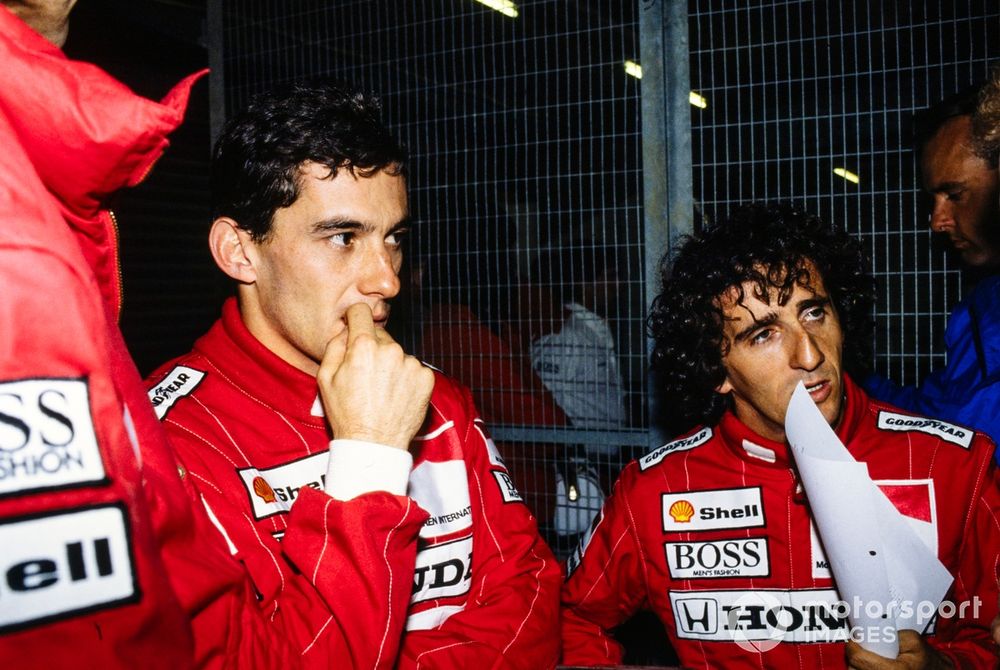

The most compelling sports stories involve an evolving narrative. They build up over time, whether it’s spanning years – like the legendary rivalries of Alain Prost versus Ayrton Senna or Muhammad Ali versus Joe Frazier – throughout a season, or during a specific event. In motor racing, that progression unfolds across a race weekend, from practice sessions and qualifying to the race itself, regardless of whether a warm-up is included. For a boxing match, this timeline can extend to the pre-fight hype and the weigh-in.

Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost.

Photo by: Ercole Colombo

To further support my point, consider the enduring appeal of Test cricket, a five-day affair when a match runs its full course, despite the rise of shorter formats of the game. And I don’t hear anyone advocating for men’s matches at the tennis Grand Slams to be reduced from a best-of-five sets format to three. It’s also worth mentioning that a reimagined version of tennis matches, known as the Ultimate Tennis Showdown, hasn’t gained significant traction.

And I haven’t even brought up the Le Mans 24 Hours yet, which is the pinnacle race in my view, and arguably in the world.

Perhaps I’m outdated, and my expectations for a sporting event differ from those of someone half my age. Liberty Media seems to believe so, and furthermore, Domenicali is likely focusing on audiences consuming F1 races through screens, rather than those attending in person.

However, I wanted to contribute my thoughts to the discussion about refreshing the grand prix weekend format. I understand that the morning warm-up is a relic of the past, but I have fond memories of it. I also appreciate that it gave me the opportunity to witness the Lotus 80 in action with a legendary driver at the helm.

And what about that Piquet fan at Paddock in ’83? I wonder if he remembers the morning warm-up with the same fondness.

In this article

Be the first to know and subscribe for real-time news email updates on these topics