For the numerous enthusiasts who gathered at the stands, eager to cheer on the Maranello team, the true revelation of the Monza weekend proved, unfortunately, to be not Ferrari, but rather Red Bull. For the Italian squad, it represented a disappointing outcome; the Formula 1 Italian Grand Prix was perceived as one of their most promising chances to overcome the leading team, Red Bull.

However, this did not transpire. Monza, where aerodynamic performance is paramount, highlighted the weaknesses within the Ferrari package which have been evident for much of the racing year, even on a course believed to suit it’s strengths. Expectations of securing a maiden victory this season were effectively curtailed on the Saturday, following a qualifying session where the SF-25 lacked the outright speed to take the lead.

To realistically aim for a result beyond fourth and sixth positions, a fortunate change of events on Sunday would be required. The drivers pushed from the start of the race to try and make that happen but, with few influencing events emerging, hopes gradually diminished.

The grand prix ultimately followed a predictable course, devoid of unexpected incidents, surpassing even the teams’ own expectations. The variables that had introduced doubt the prior year, and which could have potentially aided Ferrari, failed to materialise. This exposed the areas where the SF-25 lagged behind its competitors, notably in terms of aerodynamic efficiency.

This deficiency confined Ferrari to a supporting role in a grand prix they were hoping to play a leading part in. The initial indications appeared during the qualifying session, but in the race itself, deprived of the additional adhesion from the fresh soft tyres, the SF-25’s limitations became more obvious.

Undeniably, in the initial stages of the event, both drivers accelerated, leading to overheating in their tyres at a sensitive juncture of their lifespan. The drivers required several laps to restore equilibrium, but the effect was minimal, without greatly affecting wear and with degradation remaining low.

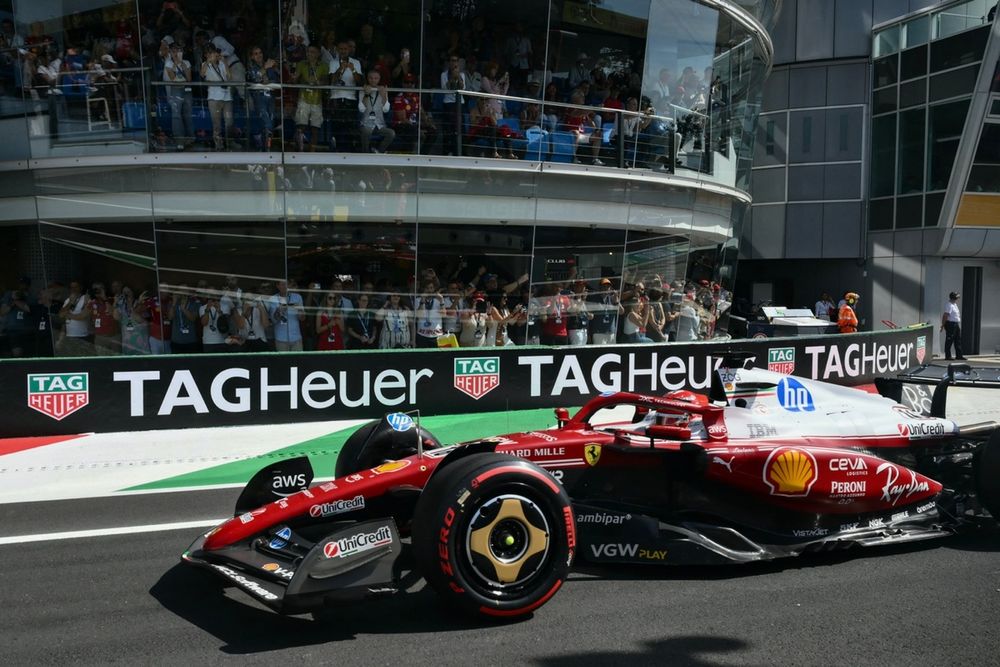

Charles Leclerc, Ferrari, Oscar Piastri, McLaren, George Russell, Mercedes

Photo by: Andy Hone/ LAT Images via Getty Images

Fred Vasseur noted during his post-race comments the deficit of a “final tenth” in direct comparison to McLaren. This assertion holds true concerning a single, unimpeded lap, regardless of the fact that the new soft compound tyres masked a few shortcomings, assisting an aerodynamic setup already set for low drag. During the race, the situation changed significantly, diverging considerably from expectations. As a result, Ferrari lacked the essential components required to succeed at the Temple of Speed.

Analysing data from lap 20 onwards, following the peak stage concerning thermal management, it becomes apparent where the SF-25 was losing to McLaren and Red Bull: through the bends. More specifically, within the faster and most demanding portions such as Ascari and Parabolica, where steadiness is critical, the Ferrari sometimes trailed by around 10-11km/h.

The appreciable pace gain on the straights, reaching up to 6-7 km/h versus the MCL39 and 3-4 km/h relative to the RB21, did not sufficiently offset the seconds surrendered in the turns, contributing to a median shortfall of approximately two and a half tenths of a second per lap relative to Piastri, and beyond four against Verstappen, up to the initial pitstop.

On a positive note, it was this reduced speed through the corners that helped the SF-25 put less pressure on the tires, helping a steady gain in speed during the closing stint, until levels of performance came close to rivals.

By navigating curves at a slower rate, the SF-25 lessened the stress applied to the tires, proving helpful during the central stages of the race. It was at this juncture, as Verstappen mentioned, that he began to experience some consequences of degradation following over 30 laps of pushing. Ferrari faced a parallel scenario in Jeddah: hold-ups in traffic softened the rate of tire wear, again on a circuit marked by reduced degradation and smooth surfaces.

Ferrari’s strategy to favour a very streamlined arrangement is understandable, symbolising a ‘make-or-break’ technical choice, to the point that even Red Bull adopted a similar approach to gain an advantage along these lines. Prioritising a particular area was the only practical solution to overcome an all-around package such as McLaren’s MCL39. Nevertheless, the fundamental question remained the aerodynamic downforce from the undercarriage and overall structure.

Charles Leclerc, Ferrari

Photo by: Marco Bertorello / AFP via Getty Images

Over the year, the RB21 has generally excelled in high-speed corners, exhibiting a level of poise and downforce that the SF-25 was unable to equal, a point often mentioned by the drivers. This limitation was notable in numerous events, but became particularly clear, and detrimental, in Monza. Increasing the wing angle risked losing efficiency and negating one of the car’s primary strengths.

In fact, each vehicle has its own individual aerodynamic map, with certain attributes influencing efficiency dependent on both downforce and cornering. McLaren tend to be more effective and function better with increased wing angles, while Red Bull perform best with settings aimed at minimal drag.

There were expectations that the lower rear-end downforce might induce increased sliding and consequent wear to the tires. The low wear recorded, in practice, offset a key element of the MCL39’s package, its rear-end stability. That impact had the effect of equalising performance and mitigating what would otherwise have been a decisive advantage.

This series of factors allowed rival teams to push harder without significant worry, particularly at the beginning, highlighting the benefits of their aerodynamic load. Ferrari hoped Monza would serve as a setting to prove their improvement, but instead it mirrored the core shortcomings present in the SF-25.

In this article

Be the first to know and subscribe for real-time news email updates on these topics